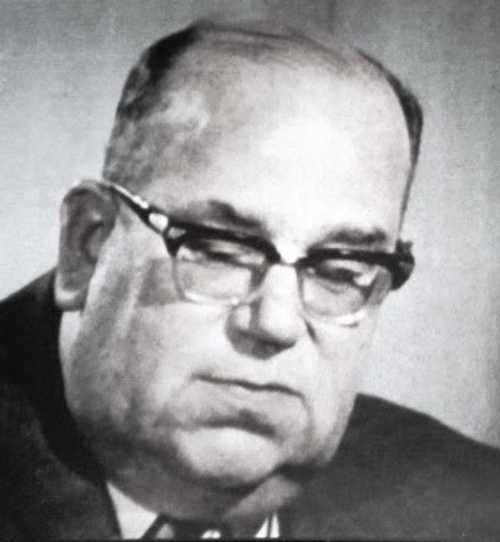

Modern/Post-War Photos

A good judge, too ?

Postwar photo of Georg Konrad Morgen, SS Judge, a still from a West German television interview. In 1933/'34, the SS was subject to a number of embarrassing legal complications, in which the Men in Black found themselves under investigation by civil legal authorities (Nazi-controlled, but political rivals) as a result of some of the more unsavory aspects of their duties. Notable among these was the case of the Dachau concentration camp, where various crimes against the inmates on the part of the rather unruly SS/SA camp administration were alleged. Perceiving, perhaps, that this sort of thing could become a perpetual source of irritation and inconvenience, the SS responded in two ways. One was to turf out the Dachau delinquents, and replace them with Theodor Eicke and his newly-minted SS-Totenkopfverbande, who replaced random, disorderly cruelty with ordered, rules-based, predictable cruelty, in line (more or less) with the principles of Legal Positivism that permeated German law at the time. I doubt whether the prisoners considered themselves any better off. The other response was to secure the removal of the SS from the jurisdiction of the civil courts. This was achieved by petitioning the Reich justice ministry to effect the removal, and to place the SS under the sole jurisdiction of the Hauptamt SS-Gericht and its courts for most purposes. The Hauptamt SS-Gericht reminds me a bit of comic historians of England, Sellar and Yeatman's summary of one provision of the Magna Carta - "that barons would only be judged by other barons, who will understand". Being an internal court system in an authoritarian organisation, the Hauptampt SS-Gericht enjoyed no "separation of powers" advantage in relation to the high SS leadership. Accordingly, while it showed extensive activity in relation to corruption, economic crime and "racial crime", it found considerable difficulty in gaining access to some of the major spheres of SS activity, notably the death/labour camp system. Also, its ability to bring home indictments against particular SS personnel, even in the economic area, was considerably inhibited by the SS version of the usual Nazi system of political and personal patronage. Higher SS officers with influence could block investigations against their "clients" simply by ordering that it be so. An example was the case of Oskar Dirlewanger. When his unit of disreputables was moved west in the face of Soviet advances, first to Poland, then to Slovakia, it was subject to a rising volume of complaints from civil administrators and Heer officers, neither of which cohort were particularly appreciative of the Dirlewanger brigade's disruptive activities. Dirlewanger was never brought to book for any of this by the SS "justice" system because his powerful protector, SS-Obergruppenfuhrer Gottlob Berger, professed to regard the complaints as ridiculous and/or exaggerated, and quashed them. This is not to say that the SS court system was completely ineffective. The SS was interested in economic crime on the part of members - for example, the misappropriation of property (such as the valuables of concentration/death camp inmates, or the fruits of their labour) that "rightly" belonged to the Reich or to the SS itself. The same could be said of corrupt abuse of position by SS members which, again, tended to divert resources due to the centre to private advantage. Also, the SS higher regions took a dim view of personal abuse (extending to murder) of SS personnel or civilians of no interest to the SS, a common circumstance where commanders were involved in embezzlement and corruption which they needed to cover up. Even here, however, much depended on personal connection. For example, Odilo Globocknik, Higher SS and Police Leader at Lublin and head of Operation Reinhard, also ran a number of forced labour camps (separate from the mass-homicidal "Reinhard" camps) largely to his own advantage. In spite of this example of corruption and embezzlement on a large scale, and an investigation by Konrad Morgen, "Globus" suffered no sanction for this behaviour; his rustication to northern Italy had more to do with his clashes with the Lublin civil administration (the deputy head of which was Himmler's brother-in-law), and even involved a promotion. Globocknik was a long-time favourite of Himmler himself, and a friend of fellow Austrian SS luminary Ernst Kaltenbrunner. By contrast, concentration camp commandant Karl-Otto Koch (husband of the infamous Ilse) was convicted of sundry irregular murders and instances of embezzlement by Judge Morgen, was sentenced to death and executed. Nobody was willing to stand up for him, apparently. Georg Konrad Morgen stands out from the SS judiciary for his indefatagable pursuit of the related phenomena of economic crime and murder within the SS. He became an SS judge in 1943, following service in the Waffen-SS. Between early 1943 and the end, he at least attempted to pursue some 800 cases against SS personnel, including complaints against Rudolf Hoess in relation to his service as commandant of Auschwitz (that, also, came to nothing). Overall, the results were (as usual) mixed, but Morgen's activity was sufficiently troubling for the SS leadership to provoke Reichsfuhrer Himmler to order him to restrain his enthusiasm at one point. Georg Konrad Morgen gave testimony in the postwar trials of Ilse Koch and others. Following his release, he resumed his legal career in West Germany. He died in 1982. Best regards, JR.

2783 Views

6/7/2013